This article was originally posted in the TWB Tech Blog on medium.com

TWB’s current research focuses on bringing language technology to marginalized communities

Translators without Borders (TWB) aims to empower people through access to critical information and two-way communication in their own language. We believe language technology such as machine translation systems are essential to achieving this. This is a challenging task given many of the languages we work with have little to no language data available to build such systems.

In this post, I’ll explain some methods for dealing with low-resource languages. I’ll also report on our experiments in obtaining a Tigrinya-English neural machine translation (NMT) model.

The progress in machine translation (MT) has reached many remarkable milestones over the last few years, and it is likely that it will progress further. However, the development of MT technology has mainly benefited a small number of languages.

Building an MT system relies on the availability of parallel data. The more present a language is digitally, the higher the probability of collecting large parallel corpora which are needed to train these types of systems. However, most languages do not have the amount of written resources that English, German, French and a few other languages spoken in highly developed countries have. The lack of written resources in other languages drastically increases the difficulty of bringing MT services to speakers of these languages.

Low-resource MT scenario

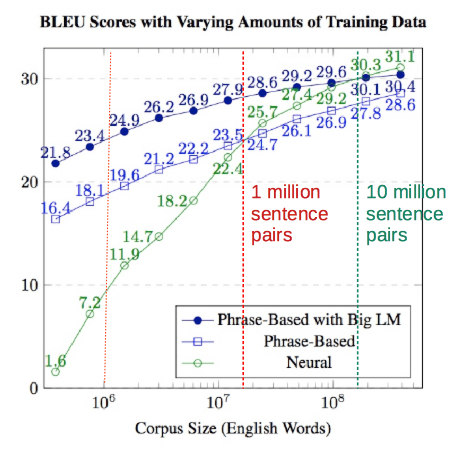

In scientific literature for machine translation, there is no particular consensus on which corpus size constitutes a low-resource scenario. But we can say roughly that a low-resource condition is when the size of the parallel training corpus is not sufficient for reaching an acceptable result with the standard MT approaches. This is usually judged with a standardized automatic evaluation metric called BLEU, which correlates with human translation assessments.

Figure 2, modified from Koehn and Knowles (2017), shows the relationship between the BLEU score and the corpus size for the three MT approaches.

A classic phrase-based MT model outperforms NMT for smaller training set sizes. Only after a corpus size threshold of 15M words, roughly equivalent to 1 million sentence pairs, classic NMT shows its superiority.

Low-resource MT, on the other hand, deals with corpus sizes that are around a couple of thousand sentences. Although this figure shows at first glance that there is no way to obtain anything useful for low resource languages, there are ways to leverage even small data sets. One of these is a deep learning technique called transfer learning, which makes use of the knowledge gained while solving one problem to apply it to a different but related problem.

Cross-lingual transfer learning

Zoph et al. (2018) applied transfer learning in machine translation and proved that having prior knowledge in translation of a separate language pair can improve translating a low-resource language.

Figure 3 illustrates their idea of cross-lingual transfer learning.

The researchers first trained an NMT model on a large parallel corpus — French–English — to create what they call the parent model. In a second stage, they continued to train this model, but fed it with a considerably smaller parallel corpus of a low-resource language. The resulting child model inherits the knowledge from the parent model by reusing its parameters. Compared to a classic approach of training only on the low-resource language, they record an average improvement of 5.6% BLEU over the four languages they experiment with. They further show that the child model doesn’t only reuse knowledge of the structure of the high resource target language but also on the process of translation itself.

The high-resource language to choose as the parent source language is a key parameter in this approach. This decision is usually made in a heuristic way judging by the closeness to the target language in terms of distance in the language family tree or shared linguistic properties. A more sound exploration of which language is best to go for a given language is made in Lin et al. (2019).

Multilingual training

The path that was cleared by cross-lingual transfer learning led naturally to the use of multiple parent languages. The straightforward approach, first described by Dong et al. (2015), mixes all the available parallel data in the languages of interest and sends them into training as illustrated in Figure 4.

What results from the example is one single model that translates from the four languages (French, Spanish, Portuguese and Italian) to English.

Multilingual NMT offers three main advantages. Firstly, it reduces the number of individual training processes needed to one, yet the resulting model can translate many languages at once. Secondly, transfer learning makes it possible for all languages to benefit from each other through the transfer of knowledge. And finally, the model serves as a more solid starting point for a possible low-resource language.

For instance, if we were interested in training MT for Galician, a low-resource romance language, the model illustrated in Figure 4 would be a perfect fit as it already knows how to translate well in four other high-resource romance languages.

A solid report on the use of multilingual models is given by Neubig and Hu (2018). They use a “massively multilingual” corpus of 58 languages to leverage MT for four low-resource languages: Azeri, Belarusian, Galician, and Slovakian. With a parallel corpus size of only 4500 sentences for Galician, they achieved a BLEU score of up to 29.1% in contrast to 22.3% and 16.2% obtained with a classic single-language training with statistical machine translation (SMT) and NMT respectively.

Transfer learning also enables what is called a zero-shot translation, when no training data is available for the language of interest. For Galician, the authors report a BLEU score of 15.5% on their test set without the model seeing any Galician sentences before.

Case of Tigrinya NMT

Tigrinya is an Ethiopian language spoken by around 7.9 million people in Eritrea and Ethiopia. It is neither supported by any commercial MT provider, nor has any publicly available models. TWB is currently developing open datasets and MT for Tigrinya in cooperation with the Masakhane initiative.

Tigrinya is no longer in the very low-resource category thanks to the recently released JW300 dataset by Agic and Vulic. Nevertheless, we wanted to see if a higher resource language could help build a Tigrinya-to-English machine translation model. We used Amharic as a parent language, which is written with the same Ge’ez script as Tigrinya and has larger public data available.

The datasets that were available to us at the time of writing this post are listed below. After JW300 dataset, the largest resource to be found is Parallel Corpora for Ethiopian Languages.

Our transfer-learning-based training process consists of four phases. First, we train on a dataset that is a random mix of all sets totaling up to 1.45 million sentences. Second, we fine-tune the model on Tigrinya using only the Tigrinya portion of the mix. In a third phase, we fine-tune on the training partition of our in-house data. Finally, 200 samples earlier allocated aside from this corpus are used for testing purposes.

As a baseline, we skip the first multilingual training step and use only Tigrinya data to train on.

We see a slight increase in the accuracy of the model on our in-house test set when we use the transfer learning approach. The results in various automatic evaluation metrics are as follows:

Conclusion

Neural machine translation is a data-hungry technology. Although this severely reduces the possibility to expand it to the majority of the world’s languages, we can still apply various techniques to make it available to more people than if we limited ourselves to approaches tuned towards high-resource languages. Methodologies like transfer learning and linguistically informed data mixture have a role to play in helping everyone communicate in their language.

Written by Alp öktem, Computational Linguist for Translators without Borders